How harmful are ultra-processed foods, really?

Ultra-processed foods are entrenched in Singaporeans' busy routines and the country's import-reliant food ecosystem. But as global debate heats up over their health risks, experts say the case for regulating them through policy reforms is not as clear-cut as it may seem.

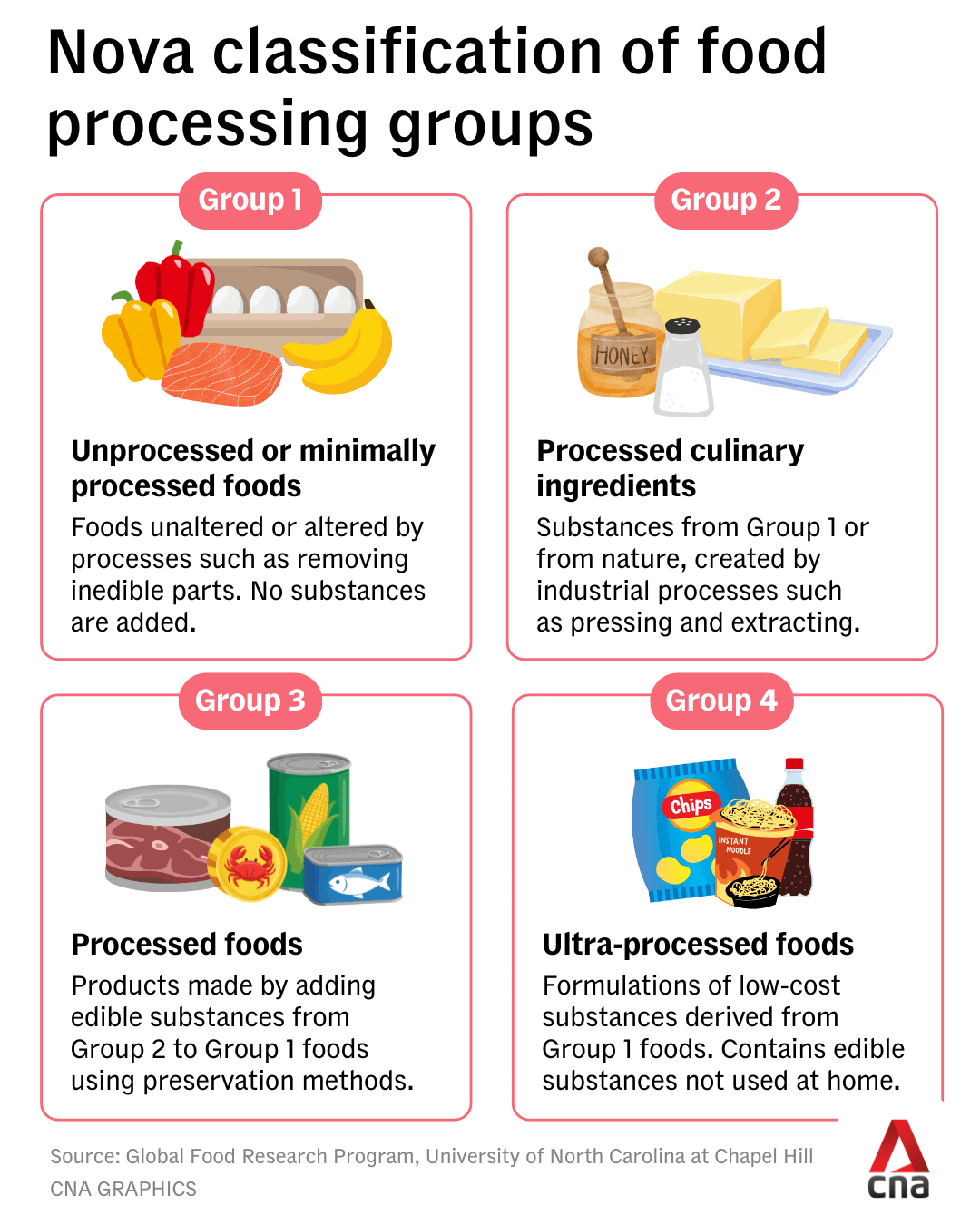

Are all ultra-processed foods bad for us? Scientists say the use of processing alone does not reflect a food's safety or nutritional value. (Illustration: CNA/Nurjannah Suhaimi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

For 35-year-old lead designer Henry Leow, instant noodles have been a staple in his diet for 25 years.

Currently living in a rented unit with limited kitchen space, Mr Leow said instant noodles are his go-to choice as they are more practical and filling than other options available to him. He usually eats them as a cheap and easy late-night meal four to five times a week, a routine that first began in childhood.

"As a kid, I would get hungry at night, especially on weekends when I got to stay up late and watch TV," he told CNA �ֻ���Ƭ��������һ����������.

"I would ask my mum to cook instant noodles, and over time, it became a habit to eat them for supper."

He is aware that it's not a healthy practice: "I've tried to cut down, but it's become such a daily habit that not eating it feels like I'm skipping a meal."

For final-year undergraduate Mohammad Afiq Ihsan Mohammad Hussien, 24, his reliance on processed foods peaked during his early university years.

While living in a university hall, he frequently turned to nearby convenience stores for quick meals such as instant noodles, microwaveable pasta and packaged sandwiches, especially during exam periods or late-night study sessions.

Convenience was his chief priority, he said. "If I'm hungry at midnight, cooking fresh food isn't realistic."

He has since cut down on ultra-processed foods (UPFs) such as fast foods, driven by health and well-being concerns. However, he admits that during busy periods, he still falls back on such foods for their convenience.

For Ms Kate Lim, a 46-year-old mother of three, ultra-processed and ready-to-eat foods are part of managing the morning rush and mealtimes without a helper. Her household staples include cereal, oats, granola, frozen bao (buns), dumplings and beef pies – items that keep well and can be prepared quickly.

Fresh ingredients, however, come with limits. "Fresh protein costs more and doesn't keep for more than three days. I'm a one-pot-wonder mummy cook, so frozen items help me save time."

Ms Lim added that her children, aged 10 to 17, also influence what ends up in the pantry.

"When my kids were younger, I was more obsessed with getting healthier options with no additives or preservatives, even if they cost more. Now that (my kids) are older, they sometimes ask for tastier, more seasoned foods, like frozen fast-food-style chicken wings that I can't fully replicate."

UPFs such as instant noodles, frozen nuggets, packaged snacks, ready-to-eat meals and sweetened beverages are popular across many demographic groups in Singapore, because they are affordable, convenient and shelf-stable.

For parents juggling work and childcare, students living in dormitories and workers with irregular hours, these products are seen as practical solutions to fill stomachs quickly and cheaply.

Last month, a group of 43 global experts published a series of papers in the Lancet medical journal calling UPFs a "major new challenge for global public health".

The authors – one of whom is the Brazilian professor who coined the term "ultra-processed foods" about 15 years ago – cited the need for "urgent, coordinated public policies and collective actions" to address the growing impact of widespread consumption of such foods.

The global proliferation of UPFs, said the authors, is strongly associated with deteriorating diet quality and higher risks of chronic illnesses such as obesity, Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and some cancers, based on consistent findings from large cohort studies and meta-analyses.

While the evidence base is still largely observational, the authors argued it meets most criteria for inferring causality, bolstered by supportive findings from short-term randomised controlled trials.

And on Wednesday (Dec 3), authorities in San Francisco, California filed a landmark lawsuit against major food manufacturers, including Coca-Cola and Kraft Heinz, alleging that their ultra-processed products contribute to chronic diseases. The case, believed to be the first of its kind in the United States, underscores the intensifying regulatory and legal scrutiny of UPFs worldwide.

But other experts CNA �ֻ���Ƭ��������һ���������� spoke to emphasised that the threat of UPFs is not as straightforward as it may seem – starting with what even counts as an "ultra-processed food".

These differing perspectives are part of an internationally contentious debate.

With UPFs playing an increasingly significant role in the average Singaporean's diet and daily routine, CNA �ֻ���Ƭ��������һ���������� explores how that role could change through regulation – or whether it should.

ARE ALL ULTRA-PROCESSED FOODS BAD FOR US?

Firstly, why is it so difficult to settle on a clear, useful definition of what counts as an "ultra-processed food"?

Experts here told CNA �ֻ���Ƭ��������һ���������� that the issue lies in the system currently being widely used to assess modern food products: Nova.

Nova was originally developed by Brazilian nutrition researchers in the late 2000s to draw attention to the rise of industrially formulated foods. The intent was not to regulate food processing itself, but to create a tool for studying broad dietary patterns and their relationship to health.

Nova aimed to introduce a new way of classifying foods. It groups foodstuffs into four categories according to the degree of processing they undergo before arriving on grocery store shelves.

Over the years, the system – which takes its name from the Portuguese word for "new" – has become the most widely used system in international UPF research. It is the framework used in hundreds of cohort studies, as well as the recent Lancet series involving 43 global experts.

Because of this, Nova has become the default reference point in media reporting and public-health advocacy.

But food scientists feel that the system is too blunt to be an effective basis for the nuanced appraisal of food products today.

For instance, Nova classifies foods solely by degree of processing rather than their formulation, purpose or nutrient profile, said Ms Mirte Gosker, chief executive officer of Good Food Institute Asia Pacific, a nonprofit think tank focused on alternative proteins headquartered in Singapore.

Ms Gosker views this as an "incomplete methodology".

In fact, food processing is a "fundamental step" in creating many of the healthy foods we enjoy today, particularly to improve safety, stability or nutritional value, she said.

A purposeful processed food is one where processing enhances safety, nutrition, or accessibility, such as fortified foods, shelf-stable staples like canned or dried items, or modern innovations like plant-based meats.

However, Nova does not distinguish these from what she calls "harmful UPFs", where much of the processing involves the addition of sugar, salt or saturated fat.

Ms Gosker said: "Alternative protein products, such as plant-based meat, are classified as UPFs under Nova, but they have a very different nutritional profile from other UPFs like processed animal meat or sugary drinks."

Dr Vinayak Ghate from the National University of Singapore noted that while many may label or perceive foods classified by Nova as "ultra-processed" as "bad", the system has little to do with how toxicologists or food scientists actually assess food safety.

Nova is not based on the fundamental scientific principle that the dose makes the poison.

"The first principle of toxicology tells us that the dose makes the poison – not whether a food is processed or natural," he said.

Dr Ghate, a lecturer in the university's Department of Food Science and Technology, said that much of the public concern stems from chemophobia – a fear of unfamiliar chemical names, such as those appearing on food labels.

"Nature itself is made up of chemicals, and everything we consume, even 'natural' foods, is a complex mix of chemicals," he said.

In food processing, he noted, new additives are typically approved only after years, sometimes decades, of rigorous testing, at concentrations far below lethal levels. This is the norm in regulatory systems worldwide.

"The important question is not whether something is a chemical, but whether it is present at a safe dose. Processed foods are regulated to contain additives only within these safe limits."

Likewise, Ms Hoo Jon Yi, lecturer in food science and technology at Singapore Polytechnic (SP), added that scientific-sounding names on labels may also seem unduly intimidating.

She pointed to E-numbers, standard additive codes which may seem like technical gibberish to a layperson. "E300, for example, is just vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid.

"Sometimes it's used to extend shelf life because it's an acid and lowers the pH. If it's in a beverage, it could also be there to make it taste slightly more sour, like a citrus note. So the function really depends on the product."

These misunderstandings aren't limited to additives – they also influence how people interpret the term "ultra-processed".

Associate Professor Lim Bee Gim from the Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) said the term "ultra-processed" is often misunderstood as a measure of how heavily a food is processed, even though Nova classifications do not account for the type or intensity of processing involved.

"A food may undergo many steps or advanced technologies like UHT (ultra-high temperature processing), retort, drying or extrusion, yet still not be classified as a UPF if it uses only home-kitchen ingredients and avoids cosmetic additives," she said, adding that this often causes public confusion.

Rather than focusing on the degree of processing alone, Good Food Institute's Ms Gosker said a more meaningful approach would be to consider nutrient composition, dietary context and the purpose of processing.

WHY UPFs ARE EVERYWHERE IN SINGAPORE

What we eat is largely seen as a personal choice. At the same time, there are structural, economic and social factors at play that make UPFs highly visible and accessible across the country.

Experts noted that UPFs dominate consumer choices not only because consumers want them, but also because our food system is organised to favour products that can travel long distances.

Singapore imports more than 90 per cent of its food, so retailers here rely heavily on consumables that can survive long supply chains with minimal quality loss. UPFs, which keep well without refrigeration, naturally fit these requirements, they said.

Importantly, they do so without relying on complex production and logistics operations.

Dr Dianna Chang, associate professor in marketing at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS), said UPFs are typically "cheap, tasty and fast-selling", made from standardised, low-cost ingredients in highly automated factories.

"Their long shelf life reduces inventory risk and wastage – an essential consideration for supermarkets operating in a high-cost environment like Singapore."

Producing these foods at scale gives businesses predictable margins, offering incentives to focus on UPFs, thereby making such products more prominent in the marketplace, said Dr Hannah Chang, associate professor of marketing at Singapore Management University (SMU).

Singapore consumers are not alone in gravitating towards UPFs – but the fast-paced life here, driven by long working hours and lengthy commutes, makes this inclination more pronounced, said experts.

Dr Hannah Chang emphasised that consumer demand and industry actions do not operate as independent forces. Instead, they are constantly reacting and responding to each other.

"Retailers respond to (consumer) preferences for convenient and affordable products, but those preferences are also shaped by advertising, promotions and prices (from retailers)."

Given the country's heavy reliance on overseas supply, processed foods – including items that would technically be classified as UPFs – are critical to the Republic's food security planning.

Healthier or fresher alternatives often require refrigeration, shorter distribution timelines and higher labour costs, making them more expensive for both retailers and consumers.

"These structural barriers are not unique to Singapore, but they are amplified in its urban, high-opportunity-cost environment," said Dr Dianna Chang.

On the other hand, processed foods reduce reliance on costly cold-chain infrastructure while keeping nutritious options accessible, said Ms Gosker from the Good Food Institute.

IS IT FEASIBLE TO REGULATE UPFs?

Globally, UPFs have become a reputational lightning rod. An analysis by consultancy firm Penta of more than 62,000 mentions across 370,000 publications globally, in more than 100 languages, found that discussions about UPFs are predominantly negative.

They are mainly driven by concerns over chronic diseases, children's diets, and calls for stricter regulations in schools, with governments, regulators and civil society groups among the most vocal critics.

The recent Lancet papers are the latest in a series of calls for countries to begin regulating ultra-processed foods in the same way they target sugar, sodium or saturated fat.

But experts told CNA that simply broadly regulating UPFs may not directly or adequately address public concerns.

A key challenge is that UPFs are not defined by specific nutrients, but by the presence of certain ingredients or industrial processes – classifications that scientists themselves often disagree on.

Dr Akshar Saxena, assistant professor of economics at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), noted that the regulatory challenge goes beyond scientific disagreement, as unclear definitions also mean unclear rules.

He pointed to a 2022 French study where food and nutrition specialists showed low overall agreement when classifying the same foods using the Nova system.

"If experts can't agree on what is ultra-processed and what isn't, regulators will struggle to set defensible rules, especially if policies are challenged," he said.

The scientific evidence underpinning UPF harm is also not as conclusive as it may seem.

Many warnings about UPFs are based on observational studies that show associations between UPF consumption and chronic illnesses, but do not establish causation, said SIT's Assoc Prof Lim, who works in translational food processing and capability development for industry. She is also the founding CEO of FoodPlant, Singapore's shared pilot-scale food production facility.

"What is more clearly supported by evidence is that diets high in sugar, salt, fat and low in fibre are linked to poorer health outcomes – regardless of how foods are categorised," she said.

SINGAPORE'S CURRENT STRATEGY

In response to queries from CNA �ֻ���Ƭ��������һ����������, a joint statement from the Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Health Promotion Board (HPB) said that ultra-processed foods currently account for less than one-third of Singapore residents' total caloric intake.

"This mirrors patterns in other Asian countries where freshly prepared foods remain common, and contrasts with Western countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States, where UPFs contribute to more than half of total calories," they said.

MOH and HPB acknowledged the negative health impacts linked to excessive consumption of UPFs, noting that highly processed products tend to have "less favourable nutrient profiles" – higher in calories, sugar, sodium, and saturated fats, and lower in fibre and essential vitamins.

Such examples include sugar-sweetened beverages, packaged snacks and processed meats, they added.

However, they emphasised that not all UPFs are nutritionally poor. Wholemeal bread, for instance, provides extra fibre, while calcium-fortified soy milk offers more protein and calcium than non-fortified options.

They added that scientific evidence remains inconclusive on whether processing techniques – such as breaking down food structures to enhance palatability – independently raise health risks beyond what can already be explained by poor nutrient profiles.

"There are currently no established international medical guidelines on recommended consumption levels for UPFs," they said.

For now, Singapore's strategy focuses on improving the broader food ecosystem and helping consumers make more informed choices, particularly foods lower in sugar, salt and saturated fat, and higher in wholegrains and protein.

Existing measures include the ban on partially hydrogenated oils, the Healthier Choice Symbol, and Nutri-Grade labelling and advertising restrictions. From mid-2027, Nutri-Grade will also be extended to key contributors of sodium and saturated fat.

They said they will continue to monitor dietary trends and assess whether the current approach effectively reduces UPF consumption.

Singapore banned partially hydrogenated oils, the main source of artificial trans fats, in 2021, removing them from all locally sold and imported foods. The Healthier Choice Symbol highlights packaged products that meet set nutritional criteria, such as being lower in sugar, sodium or saturated fat, or higher in fibre.

Nutri-Grade, introduced in 2022 for pre-packaged and freshly prepared drinks, grades beverages from "A" (lowest sugar or saturated fat) to "D" (highest). Drinks graded "D" are also subject to advertising restrictions.

Industry experts and players also cautioned that sweeping regulations focused on processing itself rather than outcomes could lead to significant unintended consequences.

Dr Saxena from NTU noted that his research shows sugar-sweetened beverages are consumed more by low-income groups, who are also more price-sensitive, and as food prices rise, budget-conscious households may shift toward cheaper, calorie-dense options, including UPFs.

"Once you tax these products, the tax becomes highly regressive. It takes up a higher share of a low-income household's budget. Balancing that burden becomes a big challenge unless there are affordable substitutes built into the system."

Trade and supply-chain constraints add further complexity for Singapore.

Mr Rory O'Donnell, a partner at consultancy Penta who specialises in agriculture, food and trade, said that Singapore aligns closely with international standards on food regulations to ensure minimal trade friction.

"If Singapore were to classify or restrict foods based on processing levels, it would need to ensure this fits with its ASEAN obligations and its trade agreements with major partners."

Any import-dependent countries mulling over food policy shifts must also consider how food supply security can be affected by global volatilities and vulnerabilities, he warned – such as recent supply chain disruptions caused by US tariffs.

Mr James Petrie, chief executive officer at food tech firm Nourish Ingredients, said overly broad rules could also stifle the very innovation needed for a healthier food system.

He called for more targeted reforms to encourage industry players to adopt cleaner formulation practices that can more effectively restore consumer trust and deliver superior health outcomes.

Ultimately, experts said a clearer, operational definition is needed before any useful UPF policies can be constructed.

Instead of overfixating on the nebulous Nova system, SIT's Assoc Prof Lim recommended weighing nutrient quality, portion size and overall dietary balance instead – considerations that are "more measurable and actionable than categorical labels based on formulation".

She pointed to existing schemes in Singapore, such as Nutri-Grade and the Healthier Choice Symbol, which already provide structured pathways for reformulation and consumer choice.

The Nutri-Grade labelling scheme was introduced in 2022 to help consumers identify beverages high in sugar or saturated fat. Drinks are graded from "A" (lowest sugar or fat) to "D" (highest sugar or fat).

Meanwhile, the Healthier Choice Symbol helps shoppers spot packaged food and drink products that meet defined nutritional criteria, such as lower in sugar and higher in dietary fibre, offering a quick way to find relatively healthier options within the same food category.

"Any policy approach should avoid confusion, avoid unintended avoidance of safe and nutritious foods, and remain evidence-based and easy for consumers to understand."

HOW TO DEVELOP HEALTHIER DIETS

With no clear regulatory definition of UPFs yet in sight, experts told CNA �ֻ���Ƭ��������һ���������� that it may not be the most practical approach for individuals to attempt to cut out UPFs entirely.

Instead, they recommended focusing on evaluating the nutritional quality of such foods, how often they are consumed, and how much of them go into each meal.

Food science experts stressed that the biggest health risks come not from processing itself, but from eating behaviour – including diets high in added sugars, refined starches, sodium, saturated fat and excess calories.

Even so, nutritionists acknowledged that it may be unrealistic to tell people to "just stop eating" their favourite unhealthy UPFs such as instant noodles and bubble tea.

Instead, they said it's more practical to help people make such choices work better for them.

Dr Kalpana Bhaskaran, president of the Singapore Nutrition and Dietetics Association, said even simple but practical tweaks can go a long way.

For instance, when preparing instant noodles, she recommended using less of the seasoning packet to reduce sodium, adding an egg or tofu to increase protein, and adding vegetables to boost fibre and micronutrients.

"All these small add-ons improve the overall nutritional profile, provide satiety and help reduce sugar spikes," said Dr Kalpana, who also heads the glycemic index research unit at Temasek Polytechnic.

The same applies to bubble tea. Dr Kalpana recommended choosing sugar levels of 0 to 30 per cent, reducing toppings such as pearls, choosing low-fat milk or teas that are lightly sweetened or unsweetened, or simply going for a smaller size.

Nevertheless, she emphasised that such improvements cannot make instant noodles or bubble tea "healthy".

Instead, it's more beneficial to reduce overall consumption of such high-sodium or high-sugar foods – even cutting back from a few times a week to once a week can make a measurable difference, said Dr Kalpana.

SIT's Assoc Prof Lim added that when choosing alternatives, it is more practical to focus on reducing nutritional risks – such as excessive sodium, sugar or saturated fat – rather than fixating on whether a product contains additives.

"Many healthier options still contain permitted stabilisers or emulsifiers, and that is acceptable. What matters more is the overall nutritional profile."

She suggested simple swaps that improve dietary quality without requiring drastic changes, such as choosing baked snacks or nuts over flavoured potato chips, or choosing fresh poultry or fish instead of processed meats like ham.

Much can also be learnt from scanning the ingredient list. Clinical nutrition manager Koh Puay Eng from food services and facilities management firm Sodexo said that comparing one product's nutritional value to another's can be as simple as looking at the first three ingredients on the label.

"In Singapore, ingredients are listed in descending order of weight, so the first three ingredients strongly influence the nutritional profile," she said. The product is likely high in calories but low in nutritional value if you spot culprits such as sugar, refined flour, refined starch, or refined oil among the first three ingredients.

At the end of the day, it's neither realistic nor necessary to avoid all foods classified as UPFs under the Nova framework, said Assoc Prof Lim.

"Overall dietary pattern matters far more than a single label or category. Guidance should support practical, sustainable habits rather than absolute avoidance."

Dr Ghate of NUS advised against seeing processing as a hidden threat.

"(Food processing) is a benign, highly regulated activity, and it will continue to be so," he said.

"We have no reason to fear processing. If anything, we should ramp up awareness of what processing truly involves, so people don't fall for misconceptions – and so we can strengthen our long-term food security."